Do you believe in ghosts?

I’ve found that ghost stories are not all that rare, but surprisingly common. I’m amazed how many people when asked if they or some family member have had encounters with ghosts report some kind of event. Here are some stories from my family about some ghostly events.

The Woman Crossing the Deck

My great-granduncle Edward Crago Bolt (1836-1894) was a sea captain, sailing three-masted cargo ships between England and the port of Freemantle on the western coast of Australia. He claimed that on one of his voyages, when he was alone on watch, he witnessed the image of a woman slowly glide across the deck, then disappear. The image he saw could not have been that of a real person as, on commercial runs, no women were permitted on board. Later when he arrived in port he learned that his wife, who had been in poor health, had died on the very day and at the very hour he had seen the apparition.

The Warning Hand

My mother’s mother, Mary Ellen Taylor, née Elliott worked in one of the shoe factories in Haverhill on Essex Street. Returning home at the end of the day, she often took a short rest, collapsing on her bed, her arms outstretched. On one particular occasion, she felt her hand clasped in the unmistakably familiar grip of her deceased mother Catherine Elliott. At the same time, her mother’s voice called, addressing her by a familiar pet name, “Mame, go to the bank!”

The incident was so vivid she could not pass it off. The following day, the story goes, Mary Ellen went to the Haverhill bank that held the mortgage to the family house at 52 High Street, and sure enough there was an imposing deadline to which she was not alerted, which, had it been missed, would have been very costly, even risking loss of the house.

The Ghostly Footfalls

Before the beginning of each semester she was to teach at Tufts University, my wife Olga would spend morning hours preparing the course syllabus. She would work in her small upstairs office at our house. I would be away, already having headed out to work.

In mid-morning she would hear, faintly at first, then louder, footsteps as from someone walking slowly back and forth overhead. The sound was distinct, though not overly loud. The attic above was unfinished, but was partially fitted out with floorboards, enough for a person—or a spirit—to walk upon.

The footfalls, Olga said, would continue for minutes at a time, stop awhile, then resume. She didn’t find them scary or threatening, but felt rather they were those of a kindly spirit watching over the house, possible those of the long-deceased head of the family that had owned the house previously. Too, our son John, who was about 10 at this time—it was the mid-to late 1980’s, would sometimes hear in his bedroom when falling asleep footsteps overhead coming from the attic area. After we had constructed an addition to the house in 1988-89, the footsteps were no longer heard, as if the spirit had concluded that the house no longer needed watching over and had passed into a new phase of being.

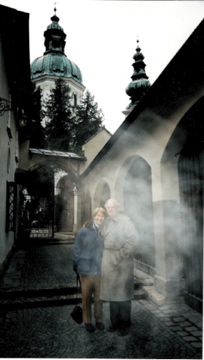

A Phantom at Salzburg?

In January 2007, my wife Olga and I were in Salzburg, Austria with family friend Béatrice, and walking through St. Peter’s Cemetery there. (St. Peter’s Cemetery is portrayed in the motion picture The Sound of Music, where Julie Andrews as Maria von Trapp and the rest of the Trapp family hide out from Nazi troops.) Béatrice took the accompanying photo of Olga and me in one of the cemetery passageways. It was early and a bit chill, with a fine morning mist about—but nothing like the cloudy swirl you see before us in the photo:

A phantom? Your guess? But given that this was within Saint Peter’s cemetery amidst the banks of tombs, I suspect so…